Modern day footballers are worshipped all over the world regardless of origins or colour, but back in London in the early eighties it was a very different story. Paul Canoville tells Footy Matters how he overcame brutal racial abuse from his own supporters, a heartbreaking career-ending injury and his battle against drugs and cancer.

Growing up in 1960s Southall, Middlesex, Paul Canoville started playing football from the age of five. His first experiences of the game were in Cherry Avenue, the street in which he lived. He went on to play for his school against other schools. Just before he started at Brentside High School he gained a little recognition as a promising young player when he appeared on local television. While at Brentside he also played with some of schoolmates for Sunday side Hanwell Celtic.

During a spell in Borstal Youth Prison he was encouraged to go for trials at Chelsea. So, on his release he signed for Hillingdon Borough, and went for trials at Southampton, Wimbledon, West Bromwich Albion and Chelsea.

At the age of 21, John Neal offered him a professional contract and he became the first black player to play for Chelsea. Unfortunately, what should have become a dream come true soon turned into an appalling nightmare when he was subjected to vicious racial abuse from his own fans on his debut, away at Crystal Palace:

“I wasn’t shocked about the abuse – I was accustomed to racial abuse having grown up in Southall. I was shocked that it was coming from fans at such an established club like Chelsea.

“The continuation of the abuse was daunting. It was close quarters and you could feel the anger from the fans, which was frightening.

“Looking back, I feel sorry for some of those fans that held that hatred. It’s even more interesting to know that some of those same fans still come up to me now and apologise for the way they conducted themselves.

“I wish that the club at the time had done a lot more about the situation. The people at the top could have done much more at the time.”

Although some of those Chelsea fans may now regret their actions and the way he was treated, fortunately his Chelsea team-mates were united in their backing of him – even if that backing was not allowed to be shown publicly.

“My team-mates were quite supportive – especially Pat Nevin. I didn’t feel that they were divided towards me. Unfortunately, my team-mates weren’t really allowed to show their support. The people at the top, again, did not want my team-mates to be drawn into discussions about my inclusion in the club.

“Whilst they weren’t hostile, they were quite naïve about my background and sometimes used to ask me questions that would be now be seen as silly.”

Despite the abuse and heartbreak he was going through, he managed to stay remarkably professional and it was his sheer passion for the game that kept him going. He now looks back at his time at Stamford Bridge with fond memories.

“It made me stronger at times and other times it made me feel sad.

“It would actually change my game sometimes and I used to wonder what more I could do to get the fans on side. Sometimes I would feel completely and utterly exasperated but my sheer love of the game and professionalism refused to allow me to let myself or the team down.

“I enjoyed it fully, it was the greatest experience I’ve ever had. For any young boy coming into the game this is a dream. What better job is there than to get paid to do something you love?”

After nearly five years he reluctantly left Chelsea and signed for Reading in 1986 before injury cruelly ended his professional career. But Paul sees his Stamford Bridge departure in a contentious light:

“Left? I don’t feel like I left, I feel like I was pushed out. I think it had more to do with an altercation with me and a team-mate and in the end they chose him over me.

“Reading welcomed me with open arms and it was really a shame that my career ended without them being able to see the full potential in me and what I could have done for the club.

“I would have pursued my career a lot longer, I would have loved to have played internationally, I might have tried my hand at coaching – the sky is the limit really. It was just unfortunate that I had to suffer an injury at such an early age of 25.”

Unable to play professionally, he returned to non-league football, but depression soon took control and he turned to drugs as an escape.

“Depression did set in after the injury. After playing for Chelsea and Reading, it took its toll. I started to take the drugs and non-league football helped to finance that. The drugs only helped forget the problems that I was thinking about but they obviously never went away.”

Drugs have not been the only battle he has faced. Having fought and beaten cancer once, it returned in 2004.

“I took the first instance of cancer very lightly – too lightly. The second time I had to stay in for a whole month and I took it much more seriously. The third time was radiotherapy this year.

“Both my battles with drugs and cancer were brought on by different things and one could argue that my drug abuse led to the cancer, but they both required me to draw on strength from somewhere. Sometimes you don’t even know how strong you are until you have no choice but to be strong.”

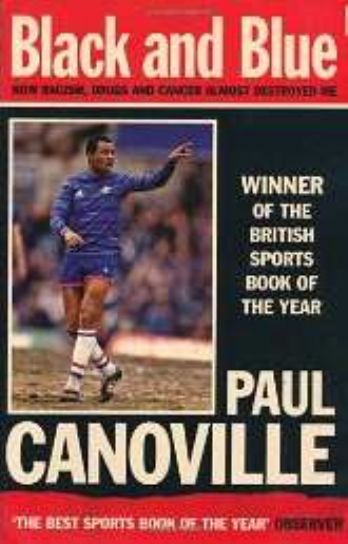

He uses his experiences (good and bad), and his battles against drugs and cancer to teach others and to help them learn from the mistakes he has made. He has also written his award-winning autobiography Black and Blue.

“I’ve just finished as a teacher’s assistant at a primary school. I now do motivational speaking, school workshops, prison workshops, working for Kick it Out, Red Card and working for Chelsea education.

“I’m just trying to educate the young people where I can, which I enjoy. I’m involved in various projects and have travelled to Germany and Geneva to talk to children about my life story and the importance of education and to address social issues like racism and bullying.

“I’ve just been recognised for my work in the community with Kick It Out and that award was presented to me at the House of Commons. I received a Black List Award in 2009 and was also awarded Best Autobiography by Sky Sports.”

He looks back on his career with fondness rather than bitterness and can be proud of what he achieved. Now, thirty years later, racism in English football grounds looks largely to be a thing of the past and clubs like Chelsea can now boast and be proud of their black players, even celebrating success under Ruud Gullit by winning the FA Cup in 1997.

“At the time all I knew was that I wanted to play and that I earned the right to play and that’s what I focused on.

“I was honoured and am honoured to be the first black player for Chelsea. But my experiences were something that I would not want any young player to ever to go through.

“Back then, I was confused about why I was treated that way, but now I look back and feel sorry for some of those people who simply didn’t know better. Society has changed so much since those days – thankfully for the better.”

Current Chelsea players such as Didier Drogba, Michael Essien and Ashley Cole are now adored by the fans rather than abused. They owe a lot of that love to Paul Canoville. I hope they realise that.

Paul Canoville's award-winning autobiography 'Black and Blue: How Racism, Drugs and Cancer Almost Destroyed Me' can be borrowed from FURD's library.